Manning formula

The Manning formula, known also as the Gauckler–Manning formula, or Gauckler–Manning–Strickler formula in Europe, is an empirical formula for open channel flow, or free-surface flow driven by gravity. It was first presented by the French engineer Philippe Gauckler in 1867,[1] and later re-developed by the Irish engineer Robert Manning in 1890.

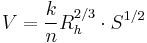

The Gauckler–Manning formula states:

where:

-

V is the cross-sectional average velocity (L/T; ft/s, m/s) k is a conversion factor of 1.486 (ft/m)1/3 for U.S. customary units, if required n is the Gauckler–Manning coefficient (T/L1/3; s/m1/3) Rh is the hydraulic radius (L; ft, m) S is the slope of the water surface or the linear hydraulic head loss (L/L) (S = hf/L)

The discharge formula, Q = A V, can be used to manipulate Gauckler–Manning's equation by substitution for V. Solving for Q then allows an estimate of the volumetric flow rate (discharge) without knowing the limiting or actual flow velocity.

The Gauckler–Manning formula is used to estimate flow in open channel situations where it is not practical to construct a weir or flume to measure flow with greater accuracy. The friction coefficients across weirs and orifices are less subjective than n along a natural (earthen, stone or vegetated) channel reach. Cross sectional area, as well as n', will likely vary along a natural channel. Accordingly, more error is expected in predicting flow by assuming a Manning's n, than by measuring flow across a constructed weirs, flumes or orifices.

The formula can be obtained by use of dimensional analysis. Recently this formula was derived theoretically using the phenomenological theory of turbulence.[2]

Hydraulic radius

The hydraulic radius is a measure of a channel flow efficiency. Flow speed along the channel depends on its cross-sectional shape (among other factors), and the hydraulic radius is a characterisation of the channel that intends to capture such efficiency. Based on the 'constant shear stress at the boundary' assumption[3], hydraulic radius is defined as the ratio of the channel's cross-sectional area of the flow to its wetted perimeter (the portion of the cross-section's perimeter that is "wet"):

where:

-

Rh is the hydraulic radius (L), A is the cross sectional area of flow (L2), P is wetted perimeter (L).

The greater the hydraulic radius, the greater the efficiency of the channel and the less likely the river is to flood. For channels of a given width, the hydraulic radius is greater for the deeper channels.

The hydraulic radius is not half the hydraulic diameter as the name may suggest. It is a function of the shape of the pipe, channel, or river in which the water is flowing. In wide rectangular channels, the hydraulic radius is approximated by the flow depth. The measure of a channel's efficiency (its ability to move water and sediment) is used by water engineers to assess the channel's capacity.

Gauckler–Manning coefficient

The Gauckler–Manning coefficient, often denoted as n, is an empirically derived coefficient, which is dependent on many factors, including surface roughness and sinuosity[4]. When field inspection is not possible, the best method to determine n is to use photographs of river channels where n has been determined using Gauckler–Manning's formula.

In natural streams, n values vary greatly along its reach, and will even vary in a given reach of channel with different stages of flow. Most research shows that n will decrease with stage, at least up to bank-full. Overbank n values for a given reach will vary greatly depending on the time of year and the velocity of flow. Summer vegetation will typically have a significantly higher n value due to leaves and seasonal vegetation. Research has shown, however, that n values are lower for individual shrubs with leaves than for the shrubs without leaves.[5] This is due to the ability of the plant's leaves to streamline and flex as the flow passes them thus lowering the resistance to flow. High velocity flows will cause some vegetation (such as grasses and forbs) to lay flat, where a lower velocity of flow through the same vegetation will not.[6]

In open channels, the Darcy–Weisbach equation is valid using the hydraulic diameter as equivalent pipe diameter. It is the only sound method to estimate the energy loss in man-made open channels. For various reasons (mainly historical reasons), empirical resistance coefficients (e.g. Chézy, Gauckler–Manning–Strickler) were and are still used. The Chézy coefficient was introduced in 1768 while the Gauckler–Manning coefficient was first developed in 1865, well before the classical pipe flow resistance experiments in the 1920–1930s. Historically both the Chézy and the Gauckler–Manning coefficients were expected to be constant and functions of the roughness only. But it is now well recognised that these coefficients are only constant for a range of flow rates. Most friction coefficients (except perhaps the Darcy–Weisbach friction factor) are estimated 100% empirically and they apply only to fully rough turbulent water flows under steady flow conditions.

One of the most important applications of the Manning equation is its use in sewer design. Sewers are often constructed as circular pipes. It has long been accepted that the value of n varies with the flow depth in partially filled circular pipes [7]. A complete set of explicit equations that can be used to calculate the depth of flow and other unknown variables when applying the Manning equation to circular pipes is available [8]. These equations account for the variation of n with the depth of flow in accordance with the curves presented by Camp.

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Gauckler, P. (1867), Etudes Théoriques et Pratiques sur l'Ecoulement et le Mouvement des Eaux, Comptes Rendues de l'Académie des Sciences, Paris, France, Tome 64, pp. 818–822

- ^ http://cee.engr.ucdavis.edu/faculty/bombardelli/PRL14501.pdf

- ^ An Introduction to Hydrodynamics & Water Waves, Bernard Le Méhauté, Springer - Verlag, 1976, p. 84

- ^ Chanson (2004)

- ^ Freeman, Rahmeyer and Copeland, http://libweb.erdc.usace.army.mil/Archimages/9477.PDF

- ^ Hardy, Panja and Mathias, http://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs/rmrs_gtr147.pdf

- ^ Camp, T. R. (1946). Design of Sewers to Facilitate Flow. Sewage Works Journal, 18: 3-16.

- ^ Akgiray, Ö. (2005). Explicit solutions of the Manning Equation for Partially Filled Circular Pipes, Canadian J. of Civil Eng., 32:490-499.

General

- Chanson, H. (2004), The Hydraulics of Open Channel Flow, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, UK, 2nd edition, 630 pages (ISBN 978 0 7506 5978 9)

- Walkowiak, D. (Ed.) Open Channel Flow Measurement Handbook (2006) Teledyne ISCO, 6th ed., ISBN 0962275735.